What Does 'Evidence-Based Practice' Really Mean?

A quick Google search of “evidence-based practices” (EBP) returns over ten million results. A more refined search of “evidence-based practices” + “substance use disorder” still generates over 750,000 results. It’s easy to understand why the term has grown so popular. It has connotations of rigor and authority, not to mention a hyphen. The devastation wrought by the U.S. opioid epidemic has pushed this issue to the forefront. Patients, insurers, regulators, and advocacy groups are all pushing for greater use of EBPs. But what does ‘evidence-based practice’ really mean? What exactly is the evidence upon which the practice is based? How strong is that evidence? How do EBP’s get from research into practice?

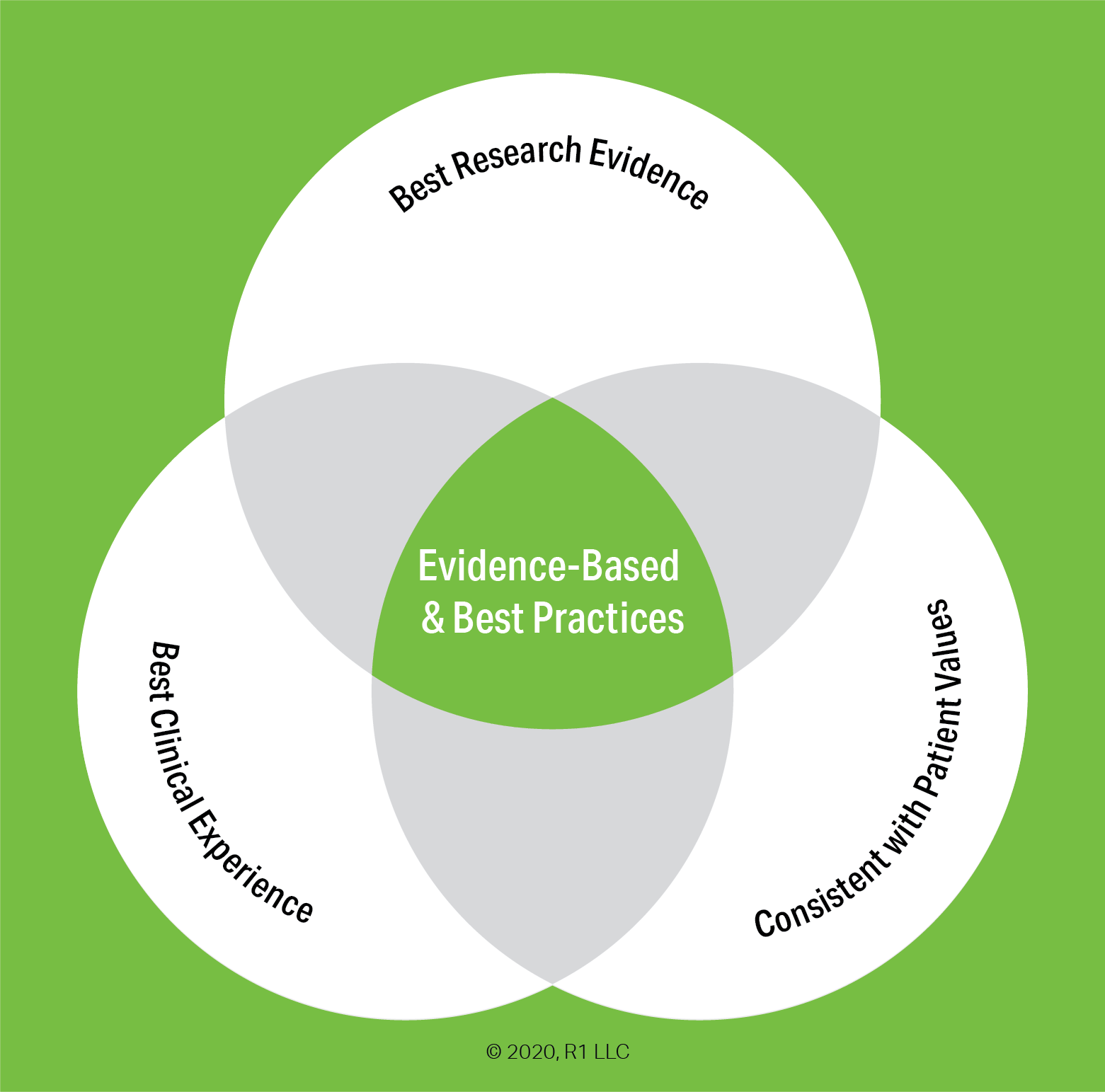

Put simply, the term ‘evidence-based practice’ means a practice or treatment, “that has been scientifically tested and subjected to clinical judgment and determined to be appropriate for the treatment of a given individual, population, or problem area.” (1)

However, the use of EBP is far more complex than that concise definition implies. Despite the widespread use of the term, conventional wisdom holds that treatments for substance-use disorders, and mental health more broadly, are not using evidence-based practices to a sufficient degree. Per the Surgeon General’s 2016 report, Facing Addiction in America:

“The addition of services to address substance use problems and disorders in mainstream health care has extended the continuum of care, and includes a range of effective, evidence-based medications, behavioral therapies, and supportive services. However, a number of barriers have limited the widespread adoption of these services, including lack of resources, insufficient training, and workforce shortages. This is particularly true for the treatment of those with co-occurring substance use and physical or mental disorders.” (2)

Over the next several weeks, the R1 Learning Blog will be looking at these issues and others in a series of posts. Concurrent with the blog series, we have added a new section on the R1 Learning website - The Evidence Base page will host a growing collection of studies and other literature on evidence-based practices, including research around overarching issues such as implementation and public policy, as well as highlighting the evidence base for specific treatment strategies. The blog series and the website additions strive to address several big questions:

What exactly does the term ‘evidence-based practice’ (EBP) mean?

What evidence-based practices for substance use disorder are commonly used?

How is the evidence measured and assessed?

Why aren’t these evidence-based practices more widely used?

What are the main obstacles and barriers to implementing evidence-based practices?

Background of EBP for Substance Use Disorder

Although the practice of medicine based on evidence has been around for centuries, treatment for mental health conditions broadly, and substance use disorder specifically, developed in specialty programs. Addiction treatment philosophy was often guided solely by the personal experience of its practitioners; similar to the, “If you want what he have, do what we do” refrain heard in Alcoholics Anonymous. This separation was reinforced by the ‘stigma’ around substance use disorders. The belief that the root causes of addiction lay in moral failings or character weakness is still alive, although great strides have been made in countering this misconception.

In the 1990s, a more formal movement emerged to push for higher standards for mental health and addiction treatment to match the standards used in primary healthcare and for the incorporation of the best available research evidence into treatment protocols. However, it was quickly observed that research evidence is very rarely a one-size-fits-all solution for mental health conditions and that the clinical experience of practitioners is of equal importance. As the Venn diagram at the top illustrates, evidence-based practices occur at the intersection of research evidence, clinical judgement, and the needs of the individual patient or population.

Below we introduce a couple of topics into which we will delve more deeply in subsequent blog posts. The Hierarchy of Evidence is the scale upon which research evidence supporting EBPs is rated and ranked. Any discussion of specific EBPs requires a basic understanding of the hierarchy of evidence and the types of studies and reports that constitute ‘evidence.’ But even the best evidence is of little utility if it isn’t faithfully put into practice. Implementation issues are often the biggest stumbling block to effectively using EBPs.

The Levels of Strength for ‘Best Research Evidence’

There are more than 80 different hierarchies for grading medical evidence, according to Wikipedia. Some are more commonly used than others. The Surgeon General’s report uses a simple 3-level convention adapted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Well-Supported, Supported, and Promising. These are good general guidelines, as the more detailed hierarchies simply break these broad categories into smaller gradations.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are considered the gold standard for evidence-based practices. A systematic review is a comprehensive review and appraisal of available studies and literature on a particular topic or treatment. As part of the review, numerical data from trials are aggregated and a statistical meta-analysis is performed.

Evidence derived from the collection of data pooled from multiple studies is held to as more robust than results of single randomized controlled trials (RCT). Studies without control groups or otherwise lacking the structure of an RCT are within the middle tiers of the hierarchy. Expert opinions, observational reports, and other anecdotal evidence is at the bottom of this scale, but is sufficient for an ‘evidence-based’ label.

A lack of systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or randomized controlled trials for a specific practice does not necessarily mean that practice is inferior or inadequate. The example of the parachute is often cited to illustrate this point. For ethical and practical reasons, there have been no randomized controlled trials proving that those wearing parachutes when jumping from an airborne plane experience greater outcomes than a control group that jumps from the same plane without parachutes. Nonetheless, wearing a parachute when exiting an airborne aircraft is unanimously considered an evidence-based best practice, as it is based on countless case reports and anecdotal observations.

Issues in Implementing Evidence-Based Practices

The existence of promising, supported, or well-supported research evidence is just one part of the issue. There is a wide chasm between the existence of evidence and the implementation of clinical practices that incorporate that research evidence.

There are a number of barriers and obstacles to effective implementation of EBP, some of which are general organizational difficulties around change, while others are specific to mental health and substance use disorder. The applicability of the research evidence is the foremost issue. The environment, population, and other factors involved in controlled trials or case studies may not neatly match those in the ‘real’ world.

This is why ‘Best Clinical Experience’ is an essential component of any evidence-based practice. Clinicians have the practical experience necessary to guide a treatment from theory to practice. Moreover, individual practitioners have a first-hand understanding of the populations they serve, the nuances of their program and mission, and the experience to foresee organizational issues that may not be apparent to researchers simply using numerical data on outcomes or studying participants in a closely controlled study.

Clinical experience is also the driver of the '‘adopt vs. adapt” decision. Adopting the evidence-based practices being pushed by stakeholders and oversight bodies sounds like the most straightforward way to implement EBPs. However, naive adoption often leads to a loss of fidelity when the practical application doesn’t match the prescriptive manual. Adapting EBPs to the specific characteristics of a program is the better decision, but also more challenging, as it requires more of practitioners. Specifically, to adapt the best research evidence to the actual clinical setting requires that those implementing the EBP have an understanding of the research evidence sufficient to tailor it to their specific populations and organizations.

We believe the ‘adopt vs. adapt’ issue is key to implementation and that successful implementation is key to the greater outcomes promised by the research evidence. The intersection of research evidence and clinical experience is the vital area of the EBP framework and we will be dedicating a post in this series specifically to the factors that influence this decision.

Questions to Explore and Next Steps

Think about your own practice, program, or organization as you look at the following questions:

What evidence-based practices are you currently using?

Are you aware of other EBPs that you would like to use?

What barriers or obstacles have you encountered in embracing or implementing evidence-based practices?

What types of tools and support would help you create greater engagement with evidence based practices?

The next post in this series will look at the major EBPs that are currently in use and/or promoted by regulators, payers, advocacy groups, and other stakeholders.

Until then, please take a look at the content on our new Evidence Base page. We have curated a selection of papers on evidence-based practices for substance use disorder in general, as well as some studies on implementation. We will be adding sections on the evidence for specific treatment modalities.

(1) Miller, Peter M., ed. Evidence-based addiction treatment. Academic Press, 2009.

(2) Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA); Office of the Surgeon General. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General's Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016 Nov.